We all knew this was coming, but the EEOC has formally determined that gender orientation is now a protected category under Title VII.

This is a significant change in the law, accomplished by fiat, rather than congressional action. In fact, Congress has consistently rejected attempts to amend Title VII to explicitly include gender orientation discrimination, raising the issue of a court challenge to the Commission's change in interpretation.

There are several potential interesting collisions here between the Commission's determination and, for example, accommodating religious practices and preferences, the abuse of discretion standard by a federal regulatory agency, and congressional review. Stay tuned, this isn't over.

Discussions on employment relationships in business, sports, the armed forces, and other odd places.

Friday, July 17, 2015

Monday, July 13, 2015

NLRB "Protected Activity" Foolishness Rejected by the DC Circuit

Two NLRB posts in a row, here, are a bit unusual, but the Board keeps making news. In this case, it's relatively good news for employers-the District of Columbia Court of Appeals has refused to enforce two separate Board rulings, both relating to the concept of "protected, concerted activity" that has provided the Board with a seemingly infinite basis to intervene in management decision-making.

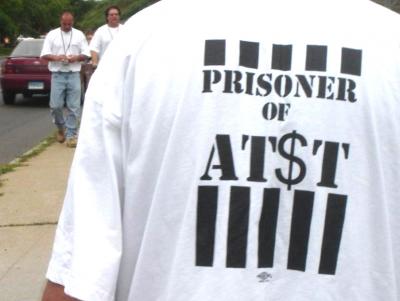

The first decision from the Court begins with an extraordinary assertion: "Common sense sometimes matters in resolving legal disputes." If only that were true more often. The Court was reviewing a situation in which AT&T refused to allow its employees who interacted with customers or worked in public (this included employees who entered customers' homes on service calls) from wearing union shirts that said, "inmate" on the front and "Prisoner of AT$T" on the back. The union, of course, was trying to make a point during contract negotiations with the company. As is frequently the case when unions reach out to engage the public in their negotiations, the conduct here was aimed, at least in part, at damaging the business's relationships with its customers.

AT&T instructed its employees who dealt with the public to remove the shirts, and when those employees refused, they received one-day suspensions. The union filed an unfair labor practice charge, and AT&T responded by arguing something called the "special circumstances" doctrine, which allows a company to ban pro-union messages on publicly visible apparel at work when the company reasonably believes the message may harm its relationship with its customers, or its public image. AT&T's position would appear to be commonsensical-nobody would want to have its employees entering customers' homes wearing shirts that said "inmate" or "prisoner".

The NLRB, however, refused to apply the doctrine, noting that no one thought the garb constituted prison wear, and therefore the company's concerns were overblown. Yeah, right. This is a singularly narrow and misleading reading of the doctrine, in my opinion, since it ignores the obvious and intentional adverse impact of having people show up in customers' homes with this kind of message on their clothing.

The Court agreed. See the reference to common sense, above. All an employer has to do is demonstrate a reasonable belief that the message can damage customer relations. That, AT&T was able to do, easily.

The second case involves an unbelievably long resolution time, but validates an important right for employers to control access to their property. In 1999 the Venetian, a luxury Vegas hotel and casino, was engaged in an organizing campaign with two unions. The unions staged a major demonstration on Venetian property and the Venetian asked the local police to issue criminal citations to demonstrators for trespass. After the unions filed unfair labor practice charges against the Venetian, the hotel argued that its request for police assistance was protected by the First Amendment-- specifically the petition principle that allows an employer to engage in conduct that would otherwise be illegal if the conduct is part of a direct petition to government for relief.

The board rejected the hotel's defense, but the Court of Appeals reversed, finding (and I don't think this is particularly controversial) that a direct petition to police for assistance falls under First Amendment protection. The Court remanded the case back to the Board to determine whether the request for police assistance was a valid one to secure property rights or whether it was a sham brought with the specific intent to further wrongful conduct through the use of governmental process.

The key for employers in this second case is to make sure that their conduct is focused on a judicially protected interest, that is, an interest that belongs specifically that the employer, before attempting to invoke this doctrine. Employers who, for example, report unionizing employees to the Department of Homeland Security for immigration purposes are not protecting their own interest. With that important caveat, the Court's guidance is clear and important, especially in union trespass situations.

Sunday, July 12, 2015

NLRB Again Makes It Harder for Employers to Manage Their Workforces

It's no secret that the National Labor Relations Board has been on a crusdade over employer investigations. The last several years have seen decisions that make it much more difficult for an employer to conduct workplace investigations, both in the union and non-union context.

Specifically, in 2014 in a case known as Fresh and Easy, the Board determined that a complaint by an individual employee relating to a personal Title VII issue (something that had little or nothing to do with the National Labor Relations Act) that triggered an employer investigation, somehow subjected that investigation to the full panoply of NLRA restrictions and requirements applicable to protected concerted activity.

Similarly, in a 2015 decision, Banner Estrela, the Board hamstrung an employer's attempt to preserve the integrity of an ongoing workplace investigation by determining that a confidentiality instruction to employees involved in the investigation violated their rights under Section 7 of the Act.

The Board continues its efforts to make it virtually impossible for an employer to conduct an effective internal investigation with its latest decision in American Baptist Homes of the West. In this case, the Board overruled a long-standing determination that employers were normally allowed to withhold from the union confidential employee statements collected as part of an investigation. Instead, employers are now required to do a case-by-case assessment of whether there is: a risk of retaliation against the employee, a high potential for witness fabrication of evidence or destruction of evidence, and similar factors, before the employer can even offer confidentiality to a prospective employee witness.

As the dissent notes, this will greatly reduce the likelihood that an employee will even talk to an employer. Most employees in a union setting are well aware of the danger for retaliation by their coworkers in a situation where they are seen to be helping the company. Until the employer hears the employee's report, it will be impossible for the employer to determine whether the circumstances are such that one of the very narrow Board standards for non-disclosure will even be met. In other words, an employer cannot offer confidentiality to a reporting employee upfront, and without that offer of confidentiality, most employees will simply elect to keep quiet rather than risk making statement that will put them in a bad position with their union leadership.

There's no question that the Board's holding damages an employer's ability to manage its workplace and its employees. It is yet another reason why the stakes on unionization of the workforce get higher each year. With the Board working to effectively limit management's ability to discover what is happening in its workforce, it is more likely that employers will simply move to workforces that cannot be unionized - independent contractors, part time employees, and task-duration hires, that are less secure and potentially pay less.

Monday, July 6, 2015

The Continuing Goofiness of Illinois Non-Compete Law

This is a terrific opinion by an Illinois intermediate appellate court that is well worth reading to get an understanding of the Grand Canyon-like fracture in Illinois noncompete agreements, and how courts are dealing with it.

The opinion lays out the application of what has recently been Illinois state courts' approach to the problem of adequate consideration for noncompete agreements, namely that an employee must be employed for at least two years after the effective date of the noncompete in order for there to be a valid contract. The dissent, brilliantly in my opinion, reviews the entire history of this odd, bright line requirement, and notes the fact that federal courts in Illinois, with one notable exception, have consistently refused to enforce this two-year requirement.

Thus, the fracture. If you are an employee seeking to avoid the consequences of signing a noncompete agreement, and you haven't been employed for two years from the date of the agreement (and you didn't receive some other form of equivalent compensation to two years of employment), then you need to make a beeline for state court to file a claim for declaratory relief. This type of claim allows the court to determine whether your noncompete is valid, and it's important that you, the employee, file before your employer figures out what's going on and files a breach of contract claim in federal court (assuming federal jurisdiction is available). Illinois state courts will almost certainly enforce the two-year bright line test; if your employer can get to federal court first, then it will likely find a judge who will refuse to enforce the standard.

This is obviously intolerable. But here in Illinois we specialize in working with the intolerable. There is a chance this divide will get fixed when the Seventh Circuit issues an opinion on a non-compete case later this year. But there's also a chance the appeals court will kick the issue over to the Illinois Supreme Court for an advisory opinion, further delaying resolution.

In the meantime, non-compete clauses require some careful thought about enforcement. I would tell employers to incorporate some type of declining bonus payout that erodes as the employee remains on the active rolls as consideration for any noncompete clause; if the employee leaves early, she gets a larger payout to support the non-compete agreement. I think this will pass muster, based on this opinion, and others like it.

UPDATE: While we wait for this all to sort out, here's a nice analysis of Illinois law regarding assessing the business interest protected by a non-compete, from the Seventh Circuit.

Sunday, July 5, 2015

No Need to Get Exhausted? 2d Circuit Opens a Door to No Charge EEO Litigation

Here's an interesting case from the federal Court of Appeals in New York concerning the requirements for exhaustion of administrative process before a lawsuit can proceed under Title VII. Plaintiff, an iron worker, alleged sex discrimination against his union based on his transgender status, along with several other federal complaints. His original charge was filed in 2007. That claim was ultimately dismissed when plaintiff failed to file his lawsuit in less than than 90 days after the EEOC gave him a right to sue letter.

Plaintiff then filed a second lawsuit in 2011, alleging similar discriminatory claims. The district court kicked this lawsuit because plaintiff fail to file an administrative charge with the EEOC for any conduct occurring after the date of the 2007 charge.

This dismissal should not be a surprise to anyone - Title VII requires a plaintiff to file an administrative charge of discrimination with the EEOC, and requires that the EEOC process be completed, before a lawsuit can move forward. In litigation parlance, this is known as "exhausting administrative remedies", and a failure to do so is generally fatal to any Title VII lawsuit.

There are certain limited exceptions to this rule - a plaintiff can allege that he was somehow prevented from filing his charge of discrimination because of actions by his employer or incompetence by the EEOC that interfered with his ability to file. Under these very limited circumstances, a plaintiff may have an equitable basis to proceed without first exhausting the administrative process.

And that's where it gets really interesting here. The Court of Appeals reversed the district court's dismissal of the gender discrimination claim, determining that it was possible that an equitable defense might exist. The equitable defense in question is a change in the law, specifically, the Court noted that after 2012, the EEOC determined that transgender discrimination was actually a form of gender discrimination and could be pursued under the statute.

I might note that when Title VII was originally passed, the prospect of gender orientation discrimination was never considered or intended by the drafters, and to this day the statute does not contain language making gender orientation a protected class. Transgender and homosexuality cases have been pursued by the EEOC on a "gender stereotyping" theory, which normally arises in a very limited set of circumstances. Plaintiff was careful to allege several of those circumstances in his later federal complaint.

So the case goes back to the district court to determine whether the plaintiff is excused from even filing a charge of discrimination on a set of facts going back 10 years because now the Commission believes that it can take these claims and process them.

This is a little disturbing, since theoretically the analysis opens the door to not only hundreds of gender orientation cases, but every other type of claim in which the executive agency's interpretation of the statue has evolved. Perhaps the appellate court did not mean that everyone with a gender orientation discrimination claim that got tossed prior to 2012 can now come back into court, but there is no limiting language in the opinion. This is another one of those situations in which I hope I'm reading too much into the Court's analysis.

Fascinating Insight Into the Hiring Process

This is a really interesting article about how hiring decisions frequently get made with respect to middle and upper level entry positions in professional organizations, such as law firms and banks.

When employment discrimination law was in its infancy, everyone recognized that a significant barrier to hiring minority candidates was the so-called "Old Boys Club" mentality in recruiting and hiring staff that essentially sought to hire people who looked like the interviewers. Apparently, notwithstanding the best efforts of the EEOC, internal training, videos, coaches, and lawsuits to eliminate this mindset, the trend is very much alive. The article documents studies showing how crucial it is to go to the right school and develop the right social mores because job interviewers who are the gatekeepers for these positions filter people immediately based on these type of factors.

If the article's conclusions are correct, then the so-called diversity efforts throughout the country are totally worthless because they focus on the wrong issue. I don't have an easy solution, but I think I have a better understanding of the problem after looking at this article and its underlying data.

Genetic Information Is Where You Find It--The Expansive GINA

Here's a worth-reading case out of the Eleventh Circuit that deals with the little-known Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, better known as "GINA". I say "little-known" not because the statue is obscure - in fact it's received plenty of publicity- but because employers as a whole seem manifestly unaware of the significant implications of the law. The case provides a useful standard for employers, and a cautionary tale about how even relatively straightforward employer enquiries can trigger statutory liability.

Plus the facts of the case are pretty entertaining. The employer shipped and stored food products for grocery stores in the area. Someone or someones unknown with a terrible sense of humor, or a bad sense of bathroom etiquette, began defecating in the company's warehouse. This is not exactly a practice that you want to encourage, particularly when you are shipping foodstuffs. The company launched an immediate investigation

Part of that investigation involved taking DNA swabs from employees in the affected warehouse and comparing them to, well, samples. The two plaintiffs were subject to this procedure, and were found not to be the culprits. However, they filed charges with the EEOC alleging that the employer violated GINA because it required them to provide genetic information and then illegally disclosed that genetic information to others.

The case eventually reached federal court, where both sides moved for summary judgment. The plaintiffs argued that the employer's use of DNA testing in the investigation was a plain violation of the language of GINA, which makes it an unlawful employment practice for "an employer to request, require, or purchase genetic information with respect to an employee." The employer argued that the term "genetic information" in the statute referred only to information relating to someone's propensity for disease or illness. This, of course, was precisely what GINA was aimed at, but the court, apparently using proper methods of statutory construction, and not the Supreme Court's method in the King v. Burwell decision, went with the plain language of the statute. The court found that the request for genetic information from the employees was a GINA violation and entered judgement for the employees.

It's worth looking at the opinion for a nice view of how statutes are supposed to be reviewed by courts, but also as a general warning to employers that any type of genetic inquiry, forensic or otherwise, is suspect under this law. Moreover, off-hand comments about family traits are prohibited, as well. See my earlier blog post about how the NFL apparently violates this rule.

Most companies remain blissfully unaware of the requirements of the statute. This opinion is a nice wake up call for all of us.

Plus the facts of the case are pretty entertaining. The employer shipped and stored food products for grocery stores in the area. Someone or someones unknown with a terrible sense of humor, or a bad sense of bathroom etiquette, began defecating in the company's warehouse. This is not exactly a practice that you want to encourage, particularly when you are shipping foodstuffs. The company launched an immediate investigation

Part of that investigation involved taking DNA swabs from employees in the affected warehouse and comparing them to, well, samples. The two plaintiffs were subject to this procedure, and were found not to be the culprits. However, they filed charges with the EEOC alleging that the employer violated GINA because it required them to provide genetic information and then illegally disclosed that genetic information to others.

The case eventually reached federal court, where both sides moved for summary judgment. The plaintiffs argued that the employer's use of DNA testing in the investigation was a plain violation of the language of GINA, which makes it an unlawful employment practice for "an employer to request, require, or purchase genetic information with respect to an employee." The employer argued that the term "genetic information" in the statute referred only to information relating to someone's propensity for disease or illness. This, of course, was precisely what GINA was aimed at, but the court, apparently using proper methods of statutory construction, and not the Supreme Court's method in the King v. Burwell decision, went with the plain language of the statute. The court found that the request for genetic information from the employees was a GINA violation and entered judgement for the employees.

It's worth looking at the opinion for a nice view of how statutes are supposed to be reviewed by courts, but also as a general warning to employers that any type of genetic inquiry, forensic or otherwise, is suspect under this law. Moreover, off-hand comments about family traits are prohibited, as well. See my earlier blog post about how the NFL apparently violates this rule.

Most companies remain blissfully unaware of the requirements of the statute. This opinion is a nice wake up call for all of us.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)