Two NLRB posts in a row, here, are a bit unusual, but the Board keeps making news. In this case, it's relatively good news for employers-the District of Columbia Court of Appeals has refused to enforce two separate Board rulings, both relating to the concept of "protected, concerted activity" that has provided the Board with a seemingly infinite basis to intervene in management decision-making.

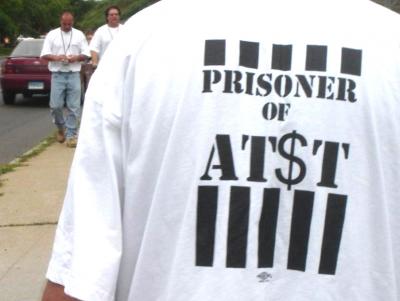

The first decision from the Court begins with an extraordinary assertion: "Common sense sometimes matters in resolving legal disputes." If only that were true more often. The Court was reviewing a situation in which AT&T refused to allow its employees who interacted with customers or worked in public (this included employees who entered customers' homes on service calls) from wearing union shirts that said, "inmate" on the front and "Prisoner of AT$T" on the back. The union, of course, was trying to make a point during contract negotiations with the company. As is frequently the case when unions reach out to engage the public in their negotiations, the conduct here was aimed, at least in part, at damaging the business's relationships with its customers.

AT&T instructed its employees who dealt with the public to remove the shirts, and when those employees refused, they received one-day suspensions. The union filed an unfair labor practice charge, and AT&T responded by arguing something called the "special circumstances" doctrine, which allows a company to ban pro-union messages on publicly visible apparel at work when the company reasonably believes the message may harm its relationship with its customers, or its public image. AT&T's position would appear to be commonsensical-nobody would want to have its employees entering customers' homes wearing shirts that said "inmate" or "prisoner".

The NLRB, however, refused to apply the doctrine, noting that no one thought the garb constituted prison wear, and therefore the company's concerns were overblown. Yeah, right. This is a singularly narrow and misleading reading of the doctrine, in my opinion, since it ignores the obvious and intentional adverse impact of having people show up in customers' homes with this kind of message on their clothing.

The Court agreed. See the reference to common sense, above. All an employer has to do is demonstrate a reasonable belief that the message can damage customer relations. That, AT&T was able to do, easily.

The second case involves an unbelievably long resolution time, but validates an important right for employers to control access to their property. In 1999 the Venetian, a luxury Vegas hotel and casino, was engaged in an organizing campaign with two unions. The unions staged a major demonstration on Venetian property and the Venetian asked the local police to issue criminal citations to demonstrators for trespass. After the unions filed unfair labor practice charges against the Venetian, the hotel argued that its request for police assistance was protected by the First Amendment-- specifically the petition principle that allows an employer to engage in conduct that would otherwise be illegal if the conduct is part of a direct petition to government for relief.

The board rejected the hotel's defense, but the Court of Appeals reversed, finding (and I don't think this is particularly controversial) that a direct petition to police for assistance falls under First Amendment protection. The Court remanded the case back to the Board to determine whether the request for police assistance was a valid one to secure property rights or whether it was a sham brought with the specific intent to further wrongful conduct through the use of governmental process.

The key for employers in this second case is to make sure that their conduct is focused on a judicially protected interest, that is, an interest that belongs specifically that the employer, before attempting to invoke this doctrine. Employers who, for example, report unionizing employees to the Department of Homeland Security for immigration purposes are not protecting their own interest. With that important caveat, the Court's guidance is clear and important, especially in union trespass situations.

No comments:

Post a Comment